X-Ray Spectral Imaging Probes How Sun-Like Plasma Blocks Light

Understanding how light interacts with matter inside stars is crucial for predicting stars’ evolution, structure, and energy output. A key factor in this process is opacity—the degree to which a material absorbs radiation. Recent experimental findings have challenged long-standing models, showing that iron, a major contributor to stellar opacity, absorbs more light than expected. This discrepancy has profound implications for our understanding of the Sun and of other stars. Over the past two decades, three groundbreaking studies [1–3] have taken major steps toward resolving this mystery, using advanced laboratory experiments to measure iron’s opacity under extreme conditions similar to those of the Sun’s interior. However, the discrepancy remained, with researchers hypothesizing that it came from systematic errors from temporal gradients in plasma properties. Now Guillaume Loisel, James Bailey, and their colleagues at Sandia National Laboratories in New Mexico present the first temporal evolution measurements of iron’s opacity using a novel fast-time-resolved x-ray detector [4]. The measurements show that temporal gradients do not resolve the model–data discrepancy. Instead, the researchers argue, the models themselves require revision.

The structure and evolution of a star depends on how the nuclear energy that is generated in the star’s center gets transported to the star’s surface. Photons are a primary energy-transfer mechanism, and the opacity of a material characterizes how transparent it is to photons. How these photons are absorbed by the stellar material is strongly influenced by atomic transitions involving bound–bound and bound–free electron transitions—and atoms with more bound electrons tend to be more absorbent. Thus, a star’s opacity depends on its heavy-element abundance.

The heavy element iron is particularly important for astrophysical opacity, even though the fractional-mass content of iron in stellar plasmas is only about 10–5 [5]. Iron retains its bound electrons at the extreme temperatures of stellar interiors, and thus researchers think its contribution to the overall opacity is critical in resolving the discrepancy between solar models and helioseismology data [6]. The agreement could be mostly restored if the opacity contributed by some heavy elements, like iron, was larger than predicted by opacity models.

For stellar interiors, the disagreement between opacity models and experiments started with a 2015 study that provided the first direct experimental evidence that iron’s opacity at stellar conditions is up to 400% higher than theoretical models predict [2]. To determine whether the discrepancy was unique to iron, the same researchers extended their opacity measurements to chromium and nickel, similarly heavy elements [3]. The findings made clear that atomic physics inside stars is rich: Some discrepancies between model and data persisted across all three elements, some were unique to chromium and iron, and some appeared only in iron.

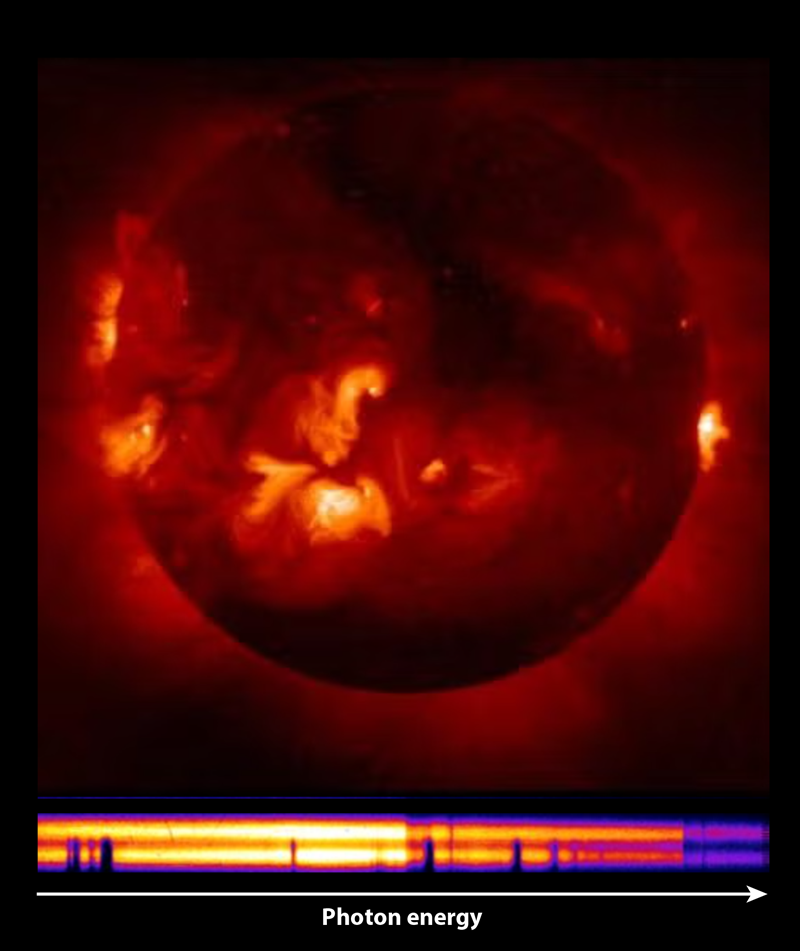

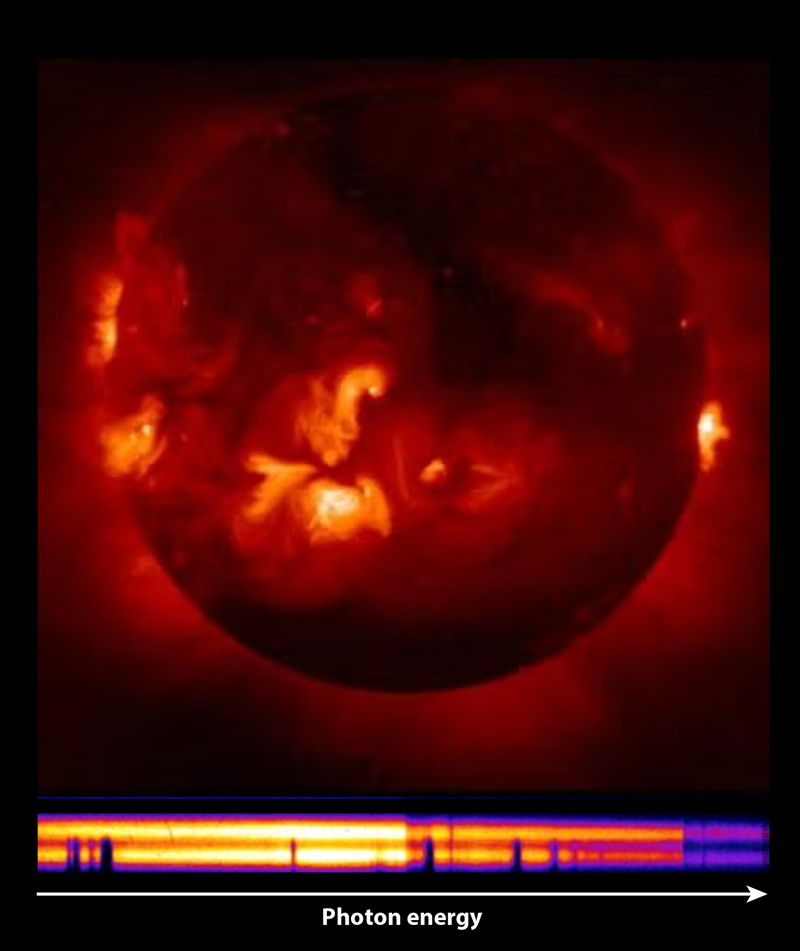

The new work by Loisel, Bailey, and colleagues introduces a new technique to the problem [4]. Experiments at the Z Pulsed Power facility (or “Z machine”) at Sandia National Laboratories infer opacity by heating a thin sample with an x-ray source. The spectrally resolved transmission is measured with spectrometers that view the x-ray source through the iron sample. X-ray spectrometers, coupled to state-of-the-art fast x-ray cameras, are used to measure the temperature and density changes in a plasma as a function of time.

The measured plasma conditions, measured x-ray time history, and modeled opacities together showed that temporal gradients do not resolve the model–data discrepancy. This finding reenforces the idea that opacity models themselves, rather than measurement techniques, need refinement. Atomic physics models thus need to be refined to account for the missing opacity.

These findings have far-reaching implications for astrophysics. If iron’s opacity is indeed higher than expected, then opacities used in stellar models need revision. This change could affect our understanding of the Sun’s energy-transport processes and the lifetime of stars. The elemental composition and opacities of the Sun are often assumed for other cosmic plasmas. Consequently, revisions in these properties of hot, dense matter could have profound implications for astrophysics. Further experiments are needed to confirm these results under an even wider range of conditions and to identify the difference between iron and other elements for which the models hold. Other high-energy-density physics facilities, such as those that employ laser-driven experiments, could provide this independent verification. Ultimately, such studies will bring us closer to solving a long-standing mystery in stellar physics, improving our ability to model not only the Sun but also stars across the Universe.

References

- J. E. Bailey et al., “Iron-plasma transmission measurements at temperatures above 150 eV,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 265002 (2007).

- J. E. Bailey et al., “A higher-than-predicted measurement of iron opacity at solar interior temperatures,” Nature 517, 56 (2015).

- T. Nagayama et al., “Systematic study of L-shell opacity at stellar interior temperatures,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 235001 (2019).

- G. P. Loisel et al., “First measurement of Z opacity sample evolution near solar interior conditions using time-resolved spectroscopy,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 095101 (2025).

- F. J. Rogers and C. A. Iglesias, “Astrophysical opacity,” Science 263, 50 (1994).

- S. Rosseland, “Note on the absorption of radiation within a star,” Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 84, 525 (1924).